This is a photo of the ceiling mural inside the chapel of Mount St. Mary University. Ligia and I were passing through the Maryland countryside on our way back from Gettysburg, we liked the architecture, and stopped to take photos. I have a ton more to postprocess, but really wanted to post this photo today since it’s Easter. The chapel was very dark and the camera couldn’t focus. I had to focus blindly, and as a result, the photo is soft. It’s also a bit noisy, since I shot at 1600 ISO. Just to round things out, I forgot my tripod at home, so I had to shoot handheld. But it gets the point across. Christ is risen indeed! Happy Easter!

Tag Archives: cameras

Camera review: FujiFilm FinePix S9100

Bottom line: love the camera body and the user interface, good lens, good grip, but the CCD sensor is not as good as it should be. Read on for the details.

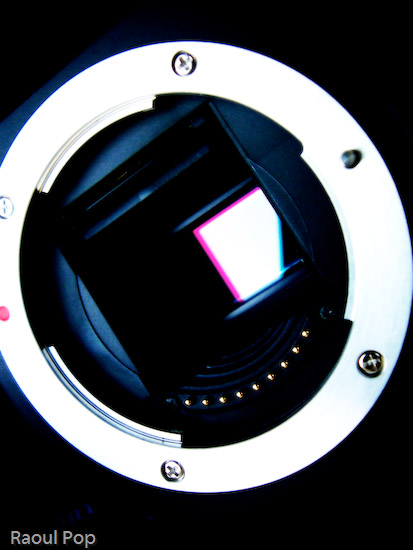

I won’t bore you with the specs, which you can check out for yourselves. I’m going to focus on real-world use. I purchased the FinePix S9100 because I wanted a good camera that would tide me over until I purchase a great DSLR (I’m eyeing the EOS 5D). I had no DSLR expectations from the S9100. I just wanted a decent digital camera with a good grip. I don’t like smallish cameras made for a woman’s hand, because they’re too light and don’t feel right in my hand. The S9100 was pretty close in dimensions to medium-sized DSLRs, and that was a strong selling point for me. I also liked the FinePix S line’s reputation. People kept saying these cameras take really good photos, and I wanted to see for myself. There were other selling points, such as the much-touted low light sensitivity, the 9 megapixel resolution, the 10x manual optical zoom, and the fact that it used AA batteries. I have a whole slew of rechargeable AA NiMH batteries at home, and I looked forward to the day when I could use them properly.

So, I got the camera this past Tuesday afternoon, and went out immediately to shoot with it. The menus of the S9100 were arranged very well, and I was able to find and set all of the options I wanted within minutes. Within 15 minutes of opening the box, I had the camera configured and the strap and lens cap attached. That made me pretty happy. I like cameras that are easy to use.

I started taking photos before getting out of the house, and that curbed my enthusiasm. The focus time was longer than I expected, comparable to and even longer than the focus on my Kodak EasyShare v610, which is a compact point and shoot. That didn’t bode well. At any rate, I pushed forward, and made it outside. The plan was to get sushi at a local restaurant with my wife, then go out into one of the local parks and take photos as the dark set in. This would give me a chance to shoot across the whole ISO range.

At the sushi place, I took more shots, and found two things that were pretty annoying. First, there was some serious lag time between shots. I shoot in RAW format, and the S9100 apparently takes a really long time to write the photo to the card. There’s no burst mode in RAW mode. You can only take one picture at a time, then wait until it gets processed and written to the card before you can take another one. I had to sit there counting second after second while the write light was on, unable to do anything else. And no, it wasn’t my card’s fault. I’ve used that card (120x CFII) with competent DSLRs like the Canon 30D and Olympus E-500, and it works beautifully. Second, when shooting at ISO 1600 inside the restaurant, there was a whole lot of noise in the shots. That really annoyed me, but I wanted to get out and take plenty of photos in the forest before I made a judgment call.

Once we got outside and I got more or less used to the long write times, using the camera was kind of nice. The flip screen was great. It allowed me to use some really interesting angles. I’d have had to guesstimate some of the shots if I only had a viewfinder to look through, since there was no way I could have craned my neck into those positions. I also liked the zoom lens. I like to twist lens barrels, I can’t help it. It gives me that tactile feel I need from my camera. The nice rubberized grip worked very well. Holding the camera in my hand, it was easy to forget that it wasn’t a DSLR. It feels very good, it’s balanced, and the buttons are just where they need to be. I had no problems using them. I loved their placement. I also loved the camera’s two Macro modes, one for closeup shots and one for really close shots of insects or other such tiny things. That’s a great feature!

As it got darker and darker, I switched to a higher ISO, and the camera worked decently up to 800 ISO in the twilight. Every time I’d switch to 1600 ISO, the noise was unbearable. But I figured, hey, I’m in the middle of a forest with no ambient light, and I’m also shooting handheld. Maybe this is to be expected. So I wrapped things up and we went back home. As we pulled into our garage, I looked at the lights in the parking lot and realized there was plenty of ambient light there to test out the 1600 ISO. I ran out, camera in hand, ready to test things, only to be disappointed once more. Every time I switched to 1600 ISO, the noise was too much, and there was serious pixel streaking going on. At the highest aperture (f2.8) and shutter speeds of 1/30 and above, there were no decent images to be gotten with the S9100, even if I stood right underneath a lamp post.

Finally, I switched it back to 100 ISO to try out some long exposure shots. I set it to a shutter speed of 4 seconds, and snuck it between the branches of a tree to stabilize it. The sky was filled with beautiful shades of blue that begged to be captured. After taking each photo, the preview screen, which is supposed to compensate for the shutter speed and show me what the photo will look like given my settings, showed me the sky exactly as I wanted it to look. I took a few shots, trying different angles, and according to the camera’s display, each photo looked fantastic. I couldn’t wait to get back inside and have a look at the photos on my computer.

After the shots were all loaded into Lightroom, Ligia and I sat at my laptop to have a look. What we noticed made us very unhappy. A lot of the shots were out of focus, even though they had seemed to be in focus on the camera’s screen. When we viewed the good shots at 100%, all of them were trashed. I have no better way of putting it. It looks like the sensor isn’t really meant for 9 megapixels. But that results in some really cheap-looking shots at full-size. Most of the detail is lost, and a whole lot of white pixels are seen instead. Really, the photos are that bad! To put things in perspective, the photos from my Kodak v610, which is a 6.1 megapixel camera released last summer, and my Panasonic Lumix FZ20K, which is a 5 megapixel camera that’s about three years old, are better than the photos from the S9100! Both of those cameras are less expensive than the S9100.

But wait, it gets better! I remembered that a cheap camera from Fuji, the FinePix A700, also uses the same 1.6-inch Super CCD HR sensor. Click on that link and see for yourselves. So what we’ve got here is a sensor from a $157 camera, being used in a camera that originally retailed for over $600. (Now it goes for about $420). That hardly seems appropriate to me, and as the say, the photos tell the truth. Have a look at a crop from one of the photos taken with the S9100 below. It’s a detail from a portrait, and it’s cropped directly in Photoshop, at 100%, with no other editing whatsoever.

Do you see what I mean? That photo’s no good, and every single one of the photos looks like this at 100%. All of the detail is gone because of that overworked sensor. Fuji might as well not have released the S9100. The inadequate sensor ruins it.

Oh, and remember those gorgeous long-exposure shots of the sky? They were all completely dark when I viewed them on my laptop. I mean pitch dark! And yet they appeared beautifully exposed on the camera’s screen. What happened? I’ll tell you: the camera can’t adjust the live preview accurately when composing the shot, and what’s worse, instead of reading the real image from the card and displaying it on the screen after taking it, it re-displays the stored live preview image instead. So I had no real way of knowing what those photos looked like when I took them. I suppose I could have switched to playback mode, but who’d have thought that the camera’s display would be this inaccurate?

After we saw all this, Ligia and I looked at each other, and we knew what had to be done. Even though I prefer to test out cameras for a month so I can get a really good feel for their usability, given the S9100’s shortcomings, there was nothing else to do but to wrap it back up and sit it nicely in its box. It’s going back. I was so disappointed. I loved the body, loved the grip, loved the zoom and ease of use, but when it came to its most important feature, the sensor, I just couldn’t live with it.

Here’s hoping Fuji sticks a good sensor in this camera at some point in the near future. Until then, my advice to you is to stay away from it.

My own sort of HDR

I’ve been intrigued by HDR (High Dynamic Range) post-processing for some time. At its best, it renders incredible images. At its worst, average, and even good, it renders completely unrealistic, overprocessed, unwatchable crud. Even some of the best images made with HDR methods seem weird. They’re not right — somehow too strange for my eyes. But, I did want to try some of it out myself and see what I’d get. The challenge for me was to keep the photo realistic and watchable. I wanted to enhance the dynamic range and color of my photos in an HDR sort of way. I also didn’t want to sit there with a tripod taking 3-5 exposures of the same scene. As much fun as that sounds, I don’t always carry a tripod with me.

By way of a disclaimer, I have not researched the production of HDR-processed images thoroughly. I have, however, seen a boatload of HDR images on both Flickr and Zooomr. I did read the tutorial that Trey Ratcliff posted on his Stuck in Customs blog. Of course, we all know Trey from Flickr, where he posts some fantastic HDR images on a daily basis. So, given my disclaimer, realize I don’t say I’m the first to have done this. I’m just saying this is how I worked things out for myself. If indeed I’m the first to do this, cool! If not, kudos to whoever did it before. I’d also like to encourage you to experiment on your own and see how things work out for you. Change my method, build on it, and make something even better. While I’m on the subject, I’m not even sure I should call this processing method HDR. It’s more like WCR (wide color range). What I’m really doing is enriching the color range already present in the photo while introducing new color tones.

When I started, I experimented with Photoshop’s built-in Merge to HDR feature. Using Photoshop, after a few non-starts that I deleted out of shame, I got something halfway usable. Have a look below.

Here’s how I processed the photo above. I shot three exposures of that scene in burst & bracket mode, handheld (no tripod), in RAW format. Then, I darkened the low exposure, lightened the light exposure, and exported all three to full-res JPGs. Used Merge to HDR in Photoshop, got a 32-bit image, adjusted the exposure and gamma, converted to 16-bit, adjusted exposure, gamma, colors, levels, highlights, then smart sharpened and saved as 8-bit JPG. It came out okay — not weird, at least not too much, anyway, but still not to my satisfaction. I should mention I also used a sub-feature of the Merge to HDR option that automatically aligned the images. As I mentioned, I shot handheld, and there were slight differences in position between the three exposures. Photoshop did a pretty good job with the alignment, as you can see above. It wasn’t perfect, but definitely acceptable.

I know there are people out there saying Photoshop doesn’t do as good a job with HDR as Photomatix. It’s possible, although I got decent results. Maybe at some point in the future I’ll give Photomatix a try, but for now, I’m pretty happy with my own method — see below for the details.

But first, what’s the point of HDR anyway? When I answered that question for myself, I started thinking about creating my own (WCR) method. The point as I see it is this: to enhance the dynamic range of my images. That means bringing out the colors, highlights and shadows, making all of the details stand out. Whereas a regular, unprocessed photo looks pretty ho-hum, an HDR-processed photo should look amazing. It should pop out, it should stand out in a row of regular images. It should not look like some teenager got his hands on a camera and Photoshop and came up with something worthy of the computer’s trash bin. As I’ve heard it from others, the standard way to postprocess a scene in HDR is to take 3-5 varying exposures, from low to high. Those exposures can then be combined to create a single image that more faithfully represents the atmosphere and look of that scene.

But, what if you don’t have a tripod with you? Can’t you use a single image? Yes, you can shoot in RAW, which is the equivalent of a digital negative, and good HDR software can use that single exposure to create multiple varying exposures, combine them and create an image that’s almost as good as the one made from multiple original exposures.

What if you want to make your own HDR/WCR images, in Photoshop, all by yourself? I wanted to do that, and I think I arrived at a result that works for me. Here’s what I did. I took a single exposure of a brook in the forest, which you can see below, unprocessed.

There’s nothing special about this photo. It’s as the camera gave it to me, in RAW format. The colors are dull and boring. There’s some dynamic range, and the color range is limited. It’s all pretty much made up of tones of brown. I took this single exposure, converted it to full-res JPG (but you don’t have to, you can use the RAW directly,) put it in Photoshop, created three copies of the original layer, called them Low, Medium and High, then adjusted the exposure for Low to low, left the exposure for Medium as it was, and adjusted the exposure for High to high. Then I set all of them to Overlay mode. (The original JPG, preserved in the Background layer, was left to Normal mode and was visible underneath all these layers.) The key word when talking about exposure here is subtle. Make subtle changes, or you’ll ruin the shot.

As soon as I adjusted the layers and changed them to Overlay, things looked a lot better. The dynamic range was there, it just needed to be tweaked. So I went in and adjusted the individual exposures for each layer some more to make sure parts of the photo weren’t getting washed out or ended up too dark. Then I threw a couple of adjustment layers on top for levels and colors. Finally, I duplicated the three layers and merged the duplicates, then used the smart sharpen tool. The adjustment layers were now on top of it all, followed by the merged and sharpened layer, and the three exposure-adjusted layers, which were no longer needed, but I kept them in there because I like to do non-destructive editing. Here’s the end result, exported to a JPG.

This is the sort of post-processing that pleases my eye. The details were preserved, the colors came out looking natural yet rich, and things look good overall. Even though some spots are a little overexposed, I like it and I’m happy with it. Let’s do a quick review. Using my own WCR/HDR-like method, I accomplished the following:

- Used a single RAW/JPG exposure

- Didn’t need to use a tripod, could shoot handheld

- Didn’t need special software, other than Photoshop

- Achieved the dynamic range I wanted

- The photo looks natural, at least to my eyes

- The post-processing was fairly simple and took about 30 minutes

There is one big difference between my WCR method and the usual HDR post-processing. Done right, the latter will help bring detail out of the shadows. Because of that single or multiple exposure done at +2 EV or more, spots that would normally be in the dark in a regular photo can be seen in HDR. Not so with my method. Here the darks become darker. The atmosphere thickens. The highlights become darker as well. The whole shot gains character, as I like to call it. So this is something to keep in mind.

Just to clarify things, the image above was the first result I obtained using my method. There was no redo. I then processed some more images, and got a little better at it. It’s worth experimenting with the Shadow/Highlight options for each individual layer. It helps minimize blown-out spots. It’s also very worthwhile to play with the Filter tool for each layer. This really helps bring out some nice colors. It’s sort of like taking three exposures of the same scene with different color filters. The results can be stunning if done well. You also don’t need to use three overlays. It all depends on the photo. Some photos only need one overlay, while others need four or five. Subtle changes in exposure can help bring out areas that are too dark. You can see some photos below where I used my own advice.

I hope this proves useful to those of you out there interested in this sort of post-processing. It’s my dream to see more natural and colorful photos, regardless of whatever post-processing method is used.

Camera review: Olympus EVOLT E-500 DSLR

For the past month, I’ve been testing out the E-500 DSLR from Olympus. It’s an entry-level DSLR with impressive specs for its class. These past 30 days or so, it has been my primary camera. It’s been everywhere with me, every day. I’ve used it in all sorts of conditions (indoors, outdoors, daylight, nights, cold, warm, wet and dry), and I’ve taken over 3,000 photos with it. So what I’m about to write carries a bit of weight — at least the sort conferred by such use. After you read my review, you’ll get to see sample photographs that I took with the camera. They’re at the end, so you may jump there right now if you’d like.

The E-500 feels good in the hand. It’s light (about 435 grams for the body, plus another 75-100 grams or so for the lens). It has a great grip. It just feels right when I hold it in my hand. One of my complaints with the Canon Rebel XT, another DSLR in the same class as the E-500, is that it’s too small. It feels like it was made for a woman’s hand. I can’t quite grip it right. Not so with the E-500.

My test model came with a 14-45mm, 1:3.5-5.6 kit lens. Given the sensor size and optics, this is equivalent to a 28-90mm lens on the 35mm system. While the aperture specs of the lens aren’t impressive, its optics and construction are. I’ve held other kit lenses in my hand, and they felt pretty flimsy. This one doesn’t. It has weight to it, and it’s solid. The mount is made of metal, and it feels like a quality product over all. Yes, in order to make the lens affordable, Olympus needed to pare down the specs, but they didn’t skimp on materials and optics, and I’m very glad for that.

The controls of the camera are easy to use and well-organized. It’s interesting to see how each camera manufacturer designs the interface they think is best for their cameras. Olympus chose to group most of the controls within easy reach of the right hand fingers. There is a main mode dial which can be rotated with the thumb and index finger, and a control dial right next to it that can be rotated with the thumb. Once I got used to the controls, and it took very little time, everything I needed to use frequently could be adjusted easily, and I liked that. My only gripe here is with the White Balance button, which I think is a bit close to the thumb rest and can be accidentally pressed as the camera is held. But as I used the E-500 more, my thumb learned to rest away from this button and things were fine. Incidentally, it would have been nice if the thumb rest were rubberized.

The user manual is great. I like the way the E-500 manual is laid out. It’s organized by sections and indexed well, so I can refer to specific topics right away. Things are also clearly explained, and I know all too well that’s not always the case with other user manuals.

The E-500 has some surprising features for an entry-level DSLR. I was impressed most of all with the supersonic wave filter (SSWF) sensor cleaning. Olympus was the first company to introduce this feature on its DSLRs a couple of years ago, and other companies such as Sony, Pentax and Canon have only more recently followed suit. The SSWF uses ultrasonic vibrations to shake dust off the sensor every time the camera is turned on. This reduces (and may even eliminate) the need to to clean the sensor, though your mileage may vary. It all depends on how much you’ll switch lenses, and how careful you are when you do it. In case you’re worried, the camera has a sensor-cleaning mode that lets you gain access to the sensor for manual cleanings.

I was pleased to see the camera had four bracketing modes: AE (exposure), WB (white balance), MF (manual focus) and flash. These modes let you vary (or bracket, hence their names) those characteristics when used. For example, AE bracketing will let you take three shots with varying exposures (dark, medium, light). You then choose the best one and delete or keep the others, as you wish. The other modes work the same, and they vary the other characteristics. This is useful for those situations when you’re not quite sure what will give you the best shot possible. Realize though that flash bracketing can get to be pretty annoying for your subjects if they’re people. No one likes being flashed repeatedly. So find the flash intensity that works, do it quickly, then stick with it.

The 2.5-inch LCD screen was a great addition to the E-500. It’s clear, big and displays photos very well, and for its time (2005), fairly unique. Olympus also spent time organizing the menu functions well, and after a short learning period, things are easy to find. The viewfinder is a different story, at least as far as I’m concerned. I found the display of the aperture and shutter information to be hard to read, because it was off to the side instead of at the bottom of the shot. Apparently, I’m not the only one to notice that shortcoming. I also noticed the eyecup (the little rubber piece around the viewfinder) was a little shallow for my eyes, and ambient light distracted me from my shots, particularly in daylight. Thankfully, I see that Olympus offers a bigger eyecup for folks like me.

The battery life was surprisingly good. I don’t know if my experience was a fluke, but I managed to get over 1,600 shots on a single charge, and over 400 of those shots were with flash. That’s impressive! I should clarify that on the first charge, I got only 350 shots. But then first charges on all rechargeable batteries don’t last that long. So after I drained the battery that first time and recharged it, the second charge lasted for over 1,600 photographs. And when the camera refused to take more shots because of the depleted battery, I turned it off, then back on, and squeezed more shots. I did this four times, and got an additional 30 shots with a battery that was supposed to be dead. Again, I don’t know if my experience was the norm, but if so, this would be a fantastic selling point. Yet I don’t see battery life mentioned anywhere in the Olympus literature or on their website.

I tried out the Olympus Master software included with the camera, and was less than impressed with its features. I stuck with Adobe Bridge and Photoshop for post-processing my photos thereafter. Incidentally, I wouldn’t advise you to download the photos from the camera to your computer by connecting the two with a USB cable. (This is true for just about any recent DSLR, by the way.) It’ll take forever, particularly if you shoot in RAW format. Because camera manufacturers haven’t updated their USB connectivity hardware, the most you’ll get is the equivalent of USB 1.1 speed. Get a card reader and use that instead. The speeds will be USB 2.0, and you’ll be happy.

I was disappointed to find that the camera’s ISO range only went from 100-400 natively. Yes, the sensitivity can be boosted up to 1600 in whole steps or 1/3 steps, but still, given that other cameras in its class (such as the Nikon D50 and Canon Rebel XT) offer native ISO up to 1600, the E-500 should do so as well. I should note that two noise reduction features are included on the camera. They are useful when using higher ISO settings. One is a noise filter that can be coupled with the ISO boost and works automatically, and another is a noise reduction feature that can be turned on and off as needed, regardless of the ISO setting. Although the noise filter did a good job at 400 and 800 ISO, it couldn’t help much at 1600. The noise reduction feature also wasn’t very helpful unless one used it with long exposures.

Time and time again, as I used the E-500, I found myself wishing for better low-light capability. I tend to take lots of shots in low light conditions, and I prefer not to use the flash, because it’s either disruptive or annoying. When I took photos of people, I found my friends covering their eyes or squinting. And of course, it’s not practical or desired to use the flash when doing street photography at night. Flash would ruin a neon sign, and would shed a harsh light on details best lit by ambient light. Maybe I’m just spoiled in wanting to do handheld night or low-light photography, but those are my expectations.

The autofocus works well and is fast given that it’s only a 3-point AF. That’s important because manual focus is too tedious to use by itself, unless you’re dealing with subjects that won’t move for some time. I also found that the focus ring on the kit Zuiko lens was best used for fine focus adjustments, not for everyday focusing tasks. There were, however, some occasions when the AF didn’t quite work, including daylight conditions. I was never quite sure why, but those times were few and far between. Autofocus was slower in low light, and at times, undesirably slow, by a factor of 3-7x when compared to daylight AF speeds. On the E-500, there is an option to use the flash as an autofocus illuminator (as on other DSLRs), but I didn’t find it useful. It didn’t cut down on the autofocus time at all, and only introduced a strobe-like light that preceded the shots and annoyed my friends even more. So I’d recommend that you plan for long AF times in low ambient light, and realize that you’re going to miss some photo ops because of it.

On the other hand, the built-in flash is surprisingly strong, and that’s good news for those occasions when it does need to be used. I was shocked to see it that it filled a room of 20’x20′ and provided ample light for most shots. Like other reviewers, I was surprised to see that I could not get red eyes in my subjects even if I wanted to, and even when not using the red-eye preflash.

The E-500 has a nice calendar feature built into the photo review mode that lets you view the shots you took on a particular day. I liked that a lot. I also found myself wishing for a bulk delete feature for a particular day. Here’s the scenario: say you take lots of shots, then download them to your computer, and you take more shots the next day, without realizing that you haven’t deleted the other shots first. With a bulk delete feature, you can select all of the shots from the previous day and delete them en masse, without needing to go through and selecting each by hand. But this is just wishful thinking and not a vital feature on an entry-level DSLR.

For those who need it, the E-500 has a mirror lock function that’s called Anti-Shock in the camera menu. It allows you to eliminate the minor vibration caused by the mirror movement as you press the shutter, and it’s useful for macro or night photography.

A surprising feature on this camera was the presence of two custom reset modes. Ever used a car where you could set your seat and steering positions, plus other settings, then store them? This is the same concept. You can choose to adjust certain camera functions, then store them into one of the custom resets. When you want to use those settings, you simply select that reset mode from the menu, and all other settings but yours are wiped out. This can prove useful for day/night photography, when you’d want features like the noise reduction turned off or on, respectively. Or for multiple users of the same camera.

Even though the camera is not dust and splash proof, I can tell you from direct experience that it is a sturdy camera that will work in some pretty harsh conditions. The stated operating temperature of the E-500 is supposed to be 32-100 degrees Fahrenheit. I’ve used it in temperatures as low as 10 degrees Fahrenheit, and it worked great. The user manual says the transitions between temperatures and humidities shouldn’t be sudden. Well, they were sudden, and the lenses didn’t fog up. They worked fine, and what’s more, the camera worked fine. I used it once while it was snowing. Snow accumulated on the camera and lens body, and when I got inside, it melted, leaving drops of water everywhere. I wiped them off, and the camera continued to work just great. I didn’t have a chance to use the camera in dusty or excessively warm conditions, but I certainly put it through its paces here in Washington, DC, and it hardly missed a beat.

I want to talk about the four-thirds standard for a bit (also see the Wikipedia entry for this). The E-500 is built on this standard, so a little background information will help you understand the differences between it and other DSLRs a little better.

As you may know if you own a DSLR, once you’ve bought it and invested in the various accoutrements that go along with that camera body, you’re stuck with the brand, so to speak. You’ve spent thousands of dollars on extra lenses, and if you want to switch to another brand, you’ll need to spend money not only on a new camera body, but on another set of lenses as well. That’s not fun, and most people can’t afford to switch brands, especially if they’ve invested heavily in lenses and other camera accessories like speedlights, batteries, etc. Hence, camera manufacturers are pretty happy (financially speaking) that lens lines aren’t inter-compatible (unless you use special mounts that may or may not work or give you the same image quality), because they have long-term, guaranteed customers.

Olympus came up with the four-thirds standard so they could make lenses that are interchangeable, and can be used by any other camera back built on the four-thirds standard, and they wanted to design them specifically for use in digital photography. But according to Wikipedia, the four-thirds standard isn’t entirely an open standard:

“Four Thirds is not an Open Standard, however, as it does not meet the “allowing anyone to use” criteria commonly accepted as the definition of an open standard. It also does not meet the criteria that the standard itself and any associated intellectual property be available on a Reasonable And Non-Discriminatory basis.“

So while the standard is good, Olympus needs to be more open about its use in the industry. There also seems to be a drawback. According to Wikipedia, even though the smaller sensor size allows for smaller and lighter lenses, it’s also to blame for the high noise I experienced when taking shots at higher ISO settings. Apparently the sensor just isn’t big enough to function well in low light. Whether that’s accurate, or whether this issue can be solved through creative engineering, I don’t know. What I do know is that I’m not happy with the performance of the E-500 in low light, particularly when shooting without flash, at shutter speeds above 1/25 seconds. But again, my needs are probably more stringent than those of the entry-level DSLR user.

This next point is entirely subjective, but I find the 4:3 aspect of the photographs I took with the E-500 more pleasing to the eye than the more prevalent 3:2 aspect found in most photographs. (The 3:2 aspect carries over from film photography.) Have a look at your computer monitor or TV. Chances are (unless you have a wide screen monitor or TV) that you’ve been looking at images made for the 4:3 standard for quite some time, and you didn’t even know it. This aspect ratio has been in use in that medium for decades.

The 3:2 aspect helps the photographer frame a landscape shot a little better, because it’s wider, but when I look at a vertical shot taken with that aspect, it seems as if one side is lopped off. As I said, this is entirely subjective, so I invite you to make up your own minds about it. I ask you to leave brand loyalty aside, and to judge which aspect looks better in each mode. I prefer 4:3 in portrait mode, and I’m on the fence between 4:3 and 3:2 in landscape mode.

So, given all of this camera’s features, capabilities and limitations, does it allow its user to take good photographs? I think so. I was pleased with the color reproduction and image quality. And I’m willing to let you judge this for yourselves as well. As I mentioned, I took over 3,000 photos with the camera, and I posted several of them below, at the end of my review.

Enough talking, let’s wrap things up. Overall, the E-500 is a solid DSLR. It’s sturdy, has a good grip, it’s got good battery life, and the image quality is great. I like the 4:3 aspect of the photos, and I like the fact that the lenses and body are interchangeable with other brands, although currently only Olympus, Panasonic and Leica make DSLRs and lenses based on the standard. That’s about five camera backs altogether, at widely varying prices, so there’s not a whole lot of choice, although that could change in the future. The sensor’s performance in low light is not up to my expectations, and that could or could not be related to the four-thirds standard. Time will tell. I think that it’s a bargain for its class. The current market price hovers around $650 for the body and two lenses, the one I tested and another, the 40-150mm f/3.5-4.5 zoom. I hear that’s a great lens. Bottom line: if I weren’t so bent on being able to use it in low light situations, I’d get one myself.

Here are the sample photographs, as mentioned above.

Hacking the GN calculations when using manual flash

Here’s how to hack it when you’re stumped as to what guide number to use with a manual flash. This is useful when you’re using an analog SLR that won’t sync the flash power automatically, or you’ve got a DSLR and want to fine-tune the amount of light the flash puts out. I can’t stand having to calculate this with formulas. We all may have seen this :

Aperture (f-stop) = GN X ISO/distance (in meters)

But do any of us know it by heart, or better yet, want to know it? And are we really going to take out a tape and measure the distance to the subject? I know I don’t feel like it. So how can we hack this? Well, we use what knowledge we have to ascertain the flash power we want, and then we adjust the GN (Guide Number) up or down. It works like this:

- Higher GN means more power for the flash and consequently, more light

- Higher f-stop means smaller aperture, and that translates to less light coming into the camera

- Higher ISO means better sensitivity to the light that the aperture lets in

- Higher distance means less light (remember, we’re using a flash, and the effective distance is limited)

So, what does this mean for us? Simple: we can adjust any of the four factors listed above to get the photo we want. Need more light? Boost the GN and/or the aperture. Can’t get more light, but want a better photo? Boost the ISO, but recognize the photo may be grainy. Can’t boost ISO? Decrease the distance between you and the subject.

Of course, keep in mind that when you boost aperture (choose a lower f-stop), you’ll decrease the depth of field. Think of the focus field as a loaf of bread. When you use a small aperture (large f-stop, 16 for example), you get the whole loaf in the shot. When you use a large aperture (small f-stop, 1.4 for example), you get only a slice in focus. You can effectively think of f-stops as slices of that loaf of bread. Larger f-stops means more slices. So if you’ve got objects in this photo of yours that reside at various points of focus (more slices), to keep them all in focus, you’ll need to keep the aperture fairly small (large f-stop). If you’re only interested in a particular object, by all means, increase the aperture (small f-stop), get more light that way, and use a lower GN. You’ll get more natural colors. Flash light can be harsh and wash out the nuances if overused, so the less you can use, the better off you are.

Don’t think I’ve forgotten to talk about shutter speed. Just realize that you won’t have too much flexibility there, in particular if you’re shooting handheld. Even with a tripod and manual flash, you can’t adjust the speed that much. Too slow, and any people in the photo will be blurry. Plus, the flash will be ineffective. It can’t stay lit for several seconds or more unless you use a bulb. Too fast, and you won’t get any light. Plus, if you’re syncing the flash with the camera, you’re limited by the top sync speed, which varies by camera and usually runs from 1/180 to 1/250 seconds. You’re better off playing with the other variables in the equation.

Remember, you don’t need to go to the trouble of using manual flash unless you have to. If you need to adjust flash intensity and your camera allows it, you can easily boost or decrease it through simple menu functions. Just look this up in your camera’s manual. You can usually use the +/- button, if your camera has one.

Hope this helps!