Producing (set design, lighting, filming, directing, editing) my wife’s cooking show has gotten me thinking about what comes after HD, because there obviously is a large discrepancy in resolution between full 1080p HD and properly exposed 35mm film (up to 3500p) — as I already mentioned in my post on preserving classic movies.

Yes, high definition is a huge improvement over standard definition, which in turn was a large improvement over early television signals. But televisions and VCRs, in spite of their popularity, are a dismal failure in picture quality compared to what they replaced: film reels and projectors.

Nowadays, we’ve gained some foothold back when it comes to consumer/prosumer video quality. We have ready access to video cameras that will record in HD (at various qualities, given the model and the price), and we have newer computers and televisions that will allow us to play back those videos at their native (720p or 1080p) resolutions. Even websites have begun in recent years to allow us to play back HD videos, and the quality of broadband internet connections has increased to the point where one doesn’t have to wait a half hour or more in order to download/buffer an HD video and play it properly on their computer. We can even play back HD videos from the internet directly on our televisions, thanks to standalone or built-in media players.

But if we’re to get back to the quality of 35mm film and best it, we must keep moving forward. Thankfully, some visionaries have already taken the first steps and have come up with a camera that can record at a similar-to-film resolution: the RED One, which can give us 2300p of extremely high definition digital video. It’s not quite 3000p or 3500p (which would be the equivalent of properly exposed film), but it gets us pretty close, and it’s certainly much better than 1080p.

The RED camera captures each frame of video as a 12-bit RAW image, which means we, as videographers, have much greater freedom than before when editing the video, just like photographers do when they switch from JPG to RAW files. All of a sudden, white balance, exposure, recovery, blacks, vibrance, saturation, and tone adjustments can be made with much more accuracy.

One area where I’d love to see more improvement — although I’m sure it’ll come with time — is RED’s ability to capture more color depth, say 14-bit or 16-bit. Bit depth is still an area where improvement can be made across the board when it comes to digital cameras.

But let’s leave tech specs alone, and think about how we can edit and enjoy the videos we could make with a RED camera. That’s where difficulties come in, because you see, we still can’t properly do that, certainly not with consumer, and not even with prosumer equipment. No, we’d be looking at professional equipment and serious prices. The market just hasn’t caught up.

There are no computers that can display that kind of resolution at full screen, and there are no televisions that can do it, either. TVs and computers are still caught up in the world of 720p and 1080p. And to make things even more complicated, now we’ve got to worry about 3D video, which is nice for some applications, but from my point of view, it’s a distraction, because it adds yet another barrier, another detour, on the road to achieving proper video resolution across the board. Manufacturers, TV stations and filmmakers are jumping on the 3D bandwagon, when they should be worried about resolution.

So, what costs would a filmmaker be looking at if he or she wanted to shoot at the highest possible digital resolution available today (a RED setup)? I crunched some numbers, and mind you, these are just approximations. The costs are likely to be 1.5-2x that much when you account for everything you might need. On a side note, the folks at RED and at Final Cut Pro have worked together quite a bit to ensure that we can edit RED video natively, directly in Final Cut Pro, on a Mac. See this video for an overview.

- RED One camera: $25,000

- 35mm RED lens: $4,250

- 18-85mm RED lens: $9,975

- RED LCD: $2,500

- RED CF media and cards: $1,500

- RED rig: about $2,500

- add extra $$$ for power, accessories, tripods, other media, etc.

- RED video card, for encoding and editing video: $4,750

- Mac Pro editing station: about $7,000-$12,000, depending on your needs, and you may need more than one of these, depending on how big your production is

- 30″ display: about $1,000-$3,000, depending on your needs, and you may need more than one of these as well, depending on the number of workstations and your display setup

- Final Cut Studio software: $1,000

- HDD-based storage for editing and archival: $2,000-$20,000, depending on your needs

- LTO tape or additional HDD-based storage for backup: costs will vary quite a bit here

- Specialized cinema hardware and display for showing movies at full resolution: I have no idea what this costs, but it’s likely to go into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and not every cinema has it

So at a minimum, we’d be talking about an investment of more than $60,000 in order to work with a RED setup today.

But let’s not get tied up in talking solely about RED cameras. Clearly the entire industry needs to take steps in order to ensure that videos at resolutions greater than 1080p HD can be played across all the usual devices. Unfortunately, they’re still tied up in SD and HD video. Most TV channels still transmit in SD or lower-than-SD video quality (lower than 480p). It’s true, most have always transmitted at broadcast quality (500p or better) but we’ve always had to contend with a lot of signal loss. And nowadays, we still have to pay extra for HD channels, even though they should be the norm, and we should be looking forward.

To that effect, computer displays need to get bigger and better, computer hardware needs to get faster, computer storage needs to expand, media players need to increase their processing power, televisions need to get better and bigger, and broadband internet needs to get faster, ideally around the gigabit range (see this talk from Vinton Cerf on that subject), so that full resolution, 4000K video can move across the internet easily.

For now, if I were to start working on RED, I’d still have to output to 720p or 1080p and keep my full resolution originals archived for another day, somewhere in the future, when consumer-grade electronics have evolved to the point where they can play my videos and films natively.

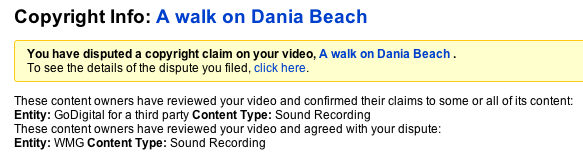

I for one look forward to the day when YouTube starts to stream 3500p videos, and when we can all play them conveniently and at full resolution on our computers and televisions!